"While the Three Gorges Dam will produce massive amounts of clean energy, the consequences of its environmental impact will take centuries to fully understand." — Wu Jun, Environmental Scientist

China's pursuit of energy dominance continues unabated, with the greenlighting of the Yarlung Tsangpo Dam—set to eclipse even the famed Three Gorges Dam. While the new dam promises to deliver up to three times the energy output of the already colossal Three Gorges, the massive resources required to construct such an ambitious project mirror the scale of China’s relentless quest for “clean energy”.

But as the world cheers on China's efforts to reduce carbon emissions, the hidden costs of these grand hydropower initiatives—both environmental and geopolitical—demand closer scrutiny. Both dams, while branded as green triumphs, come at an undeniable cost. Their construction necessitates enormous quantities of concrete, steel, and diesel, and their impacts ripple far beyond the immediate surroundings, reshaping ecosystems and altering the flow of life in ways few anticipated.

As we explore the scale of these projects, from resources to geopolitical consequences, we must ask: What is the true price of a “cleaner future”?

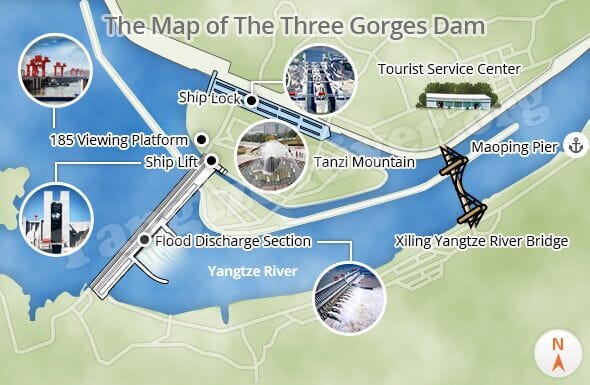

Let’s begin with the Three Gorges Dam, which, until the construction of the Yarlung Tsangpo, reigned supreme as the world’s largest hydropower station. Finished in 2012 after nearly two decades of construction, the Three Gorges Dam represents more than just a power plant; it is a symbol of China’s industrial prowess and growing influence in the global energy market.

When Beijing decided to harness the Yangtze River, the ambition was clear: create a source of massive, renewable energy to reduce the country’s reliance on coal. At 22,500 megawatts, the Three Gorges became a cornerstone of China’s energy transition. Its output helped displace millions of tons of coal each year, which had previously been burned in coal-fired plants across the country. In fact, it is estimated that the Three Gorges Dam has displaced about 100 million tons of coal annually, significantly reducing China’s dependence on coal and cutting down on CO2 emissions—initially seen as an unequivocal win for green energy.

To put it into perspective, the Three Gorges Dam required 27 million cubic meters of concrete—enough to construct 5,000 Eiffel Towers. The quantity of steel used in the dam was likewise vast, as structural reinforcements and specialized materials were needed to withstand the forces of the Yangtze River. Tens of thousands of workers—from construction crews to engineers—were employed over the course of the project, with some estimates suggesting over 200,000 people were displaced to make room for the dam’s construction and the reservoir it created.

However, as impressive as its energy production is, the Three Gorges Dam’s construction required staggering amounts of materials and resources. To put it into perspective, the Three Gorges Dam required 27 million cubic meters of concrete—enough to construct 5,000 Eiffel Towers. The amount of steel used in the dam’s construction was equally massive—over 460,000 tons of steel—needed for structural reinforcements and specialized materials to withstand the immense forces of the Yangtze River.

China relied heavily on diesel to fuel the machinery and equipment necessary to build the dam. Estimates suggest that over 100,000 tons of diesel were consumed during the construction process, powering bulldozers, cranes, trucks, and other vehicles. This reliance on diesel—fossil fuel—during construction highlights the paradox of the project: despite its role in displacing coal-fired energy, the construction itself relied on energy sources that contributed to carbon emissions.

The carbon life cycle of the Three Gorges Dam includes not only the emissions generated during construction but also the emissions associated with its long-term operation. While hydropower is generally seen as a clean energy source during operation, the life cycle emissions are still significant, particularly in the early years.

Construction Phase: During construction, as previously mentioned, 100,000 tons of diesel were consumed, along with massive quantities of concrete and steel, both energy-intensive materials to produce. The emissions from these activities alone are substantial, but they are just the beginning. Carbon emissions also resulted from the transportation of materials and the machinery used in the dam's construction.

Operational Phase: Once the Three Gorges Dam started operating, its green credentials were clear: it generates 22,500 megawatts of electricity, displacing millions of tons of coal annually and reducing carbon emissions. However, it’s important to note that the reservoir created by the dam has had its own environmental impact. The decomposition of submerged organic matter has resulted in methane emissions, a potent greenhouse gas. This is especially true in the initial years of a dam’s operation, as the organic material decomposes.

Total Carbon Footprint: Estimates of the Three Gorges Dam’s total carbon footprint—factoring in construction emissions and methane releases during operation—suggest that the dam’s long-term environmental benefits in terms of CO2 displacement are significant. Still, it can take anywhere from 10 to 50 years for the dam to offset the carbon emissions from its construction, depending on the scope of its operational efficiency and the methane levels in the reservoir.

Despite its green energy credentials, the Three Gorges Dam had unforeseen consequences. The mass of water held behind the dam—over 39 billion cubic meters—was so immense it caused a slight but measurable shift in the Earth’s axis, lengthening the day by 0.06 microseconds. While this is imperceptible to us, it serves as a reminder of the monumental scale at play when a human project intersects with the natural world.

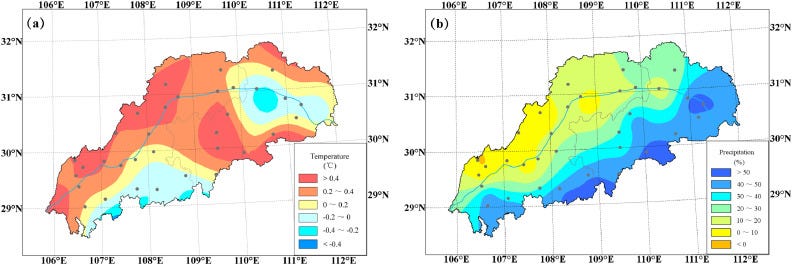

Beyond the geological effects, the Three Gorges altered regional weather patterns, shifting rainfall distribution and intensifying seasonal weather extremes. This disruption in local climate was further exacerbated by the dam’s effect on the Yangtze’s sediment transport. By preventing sediment from reaching downstream regions, soil fertility has been diminished, negatively impacting agriculture and altering local ecosystems.

In addition to these environmental shifts, the Three Gorges displaced over a million people and submerged significant cultural sites, including ancient towns and historic temples, all lost to the rising waters of the reservoir. Though a necessary trade-off for China’s energy goals, the human cost of this megaproject is incalculable.

As monumental as the Three Gorges Dam was, it is about to be dwarfed by China’s latest hydropower project: the Yarlung Tsangpo Dam. Set in Tibet’s lower reaches, the Yarlung Tsangpo (known as the Brahmaputra in its downstream course through India and Bangladesh) will be the world’s largest hydropower station once completed, with a projected output of three times the Three Gorges Dam.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Monetary Skeptic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.