In 1942, with American troops crossing oceans and factories running around the clock, the United States faced a brutal financial reality: war costs money, and lots of it. Over the course of World War II, the government spent approximately $295 billion on the war effort — the inflation-adjusted equivalent of over $5.5 trillion today. To fund this massive expenditure, tax hikes and war bond sales alone weren’t enough. The government needed to borrow unprecedented sums, but crucially, it had to do so without letting interest rates spiral out of control and blow up debt service costs.

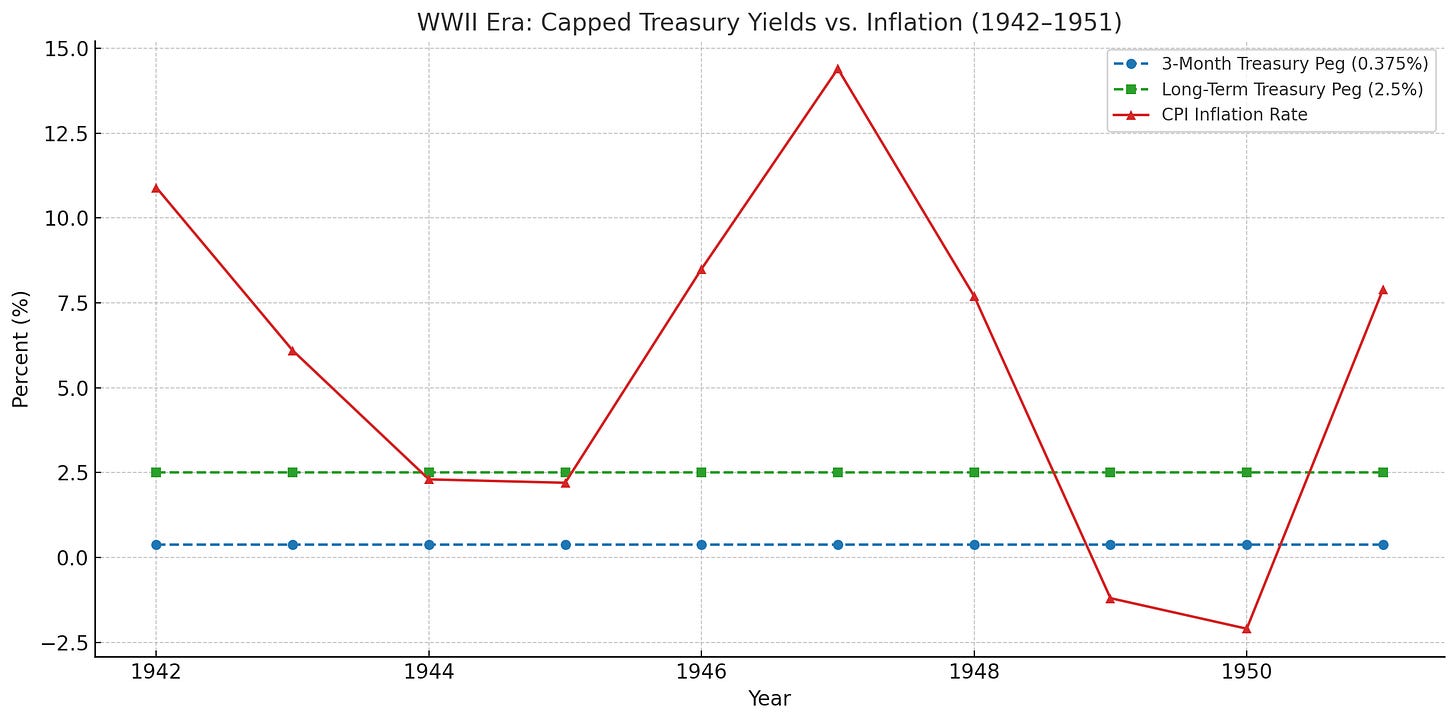

That spring, the Federal Reserve and the Treasury struck an informal yet revolutionary deal. The Fed agreed to cap short-term Treasury yields at 0.375 percent and long-term yields at 2.5 percent, pledging to buy as much government debt as necessary to enforce those ceilings. In essence, the Fed would suppress bond yields — permanently if needed — to keep borrowing costs low and debt service manageable.

This was America’s first experiment in yield curve control, a blunt form of financial repression where market forces took a backseat to political necessity.

Despite debt rising over sixfold (from $43 billion to $269 billion), debt service costs barely moved because interest rates were artificially suppressed. The government paid about $6 billion in interest in 1946 — a mere effective rate of 2.2 percent, well below what free markets would have demanded given soaring inflation.

The system held during wartime, but post-war inflation surged, breaking above 10 percent by 1948. Long-term rates, however, remained capped at 2.5 percent, creating a severe distortion. With monetary policy effectively paralyzed, the Fed pushed back.

The conflict culminated in the 1951 Treasury-Federal Reserve Accord, which formally restored Fed independence and ended the yield caps — at least on paper. But the lesson was clear: when the government needs buyers for its debt, it will either find or create them.

Fast forward 80 years. The U.S. faces a similar fiscal challenge: trillions in debt, rising deficits, and limited appetite for government bonds. Yet the tools look different — shinier, digital, and cloaked in innovation.

Enter the GENIUS Act (Generating National Interest and Uplifting Stablecoins), signed into law earlier this year. Promoted as a forward-thinking, bipartisan regulatory framework for cryptocurrencies, it carries a hidden implication for the Treasury’s debt market.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Monetary Skeptic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.