“There’s growing evidence that methane can form without biology, deep inside the Earth. We’re only beginning to understand what that means for energy.” Dr. Jürgen Kuck, German Research Centre for Geosciences

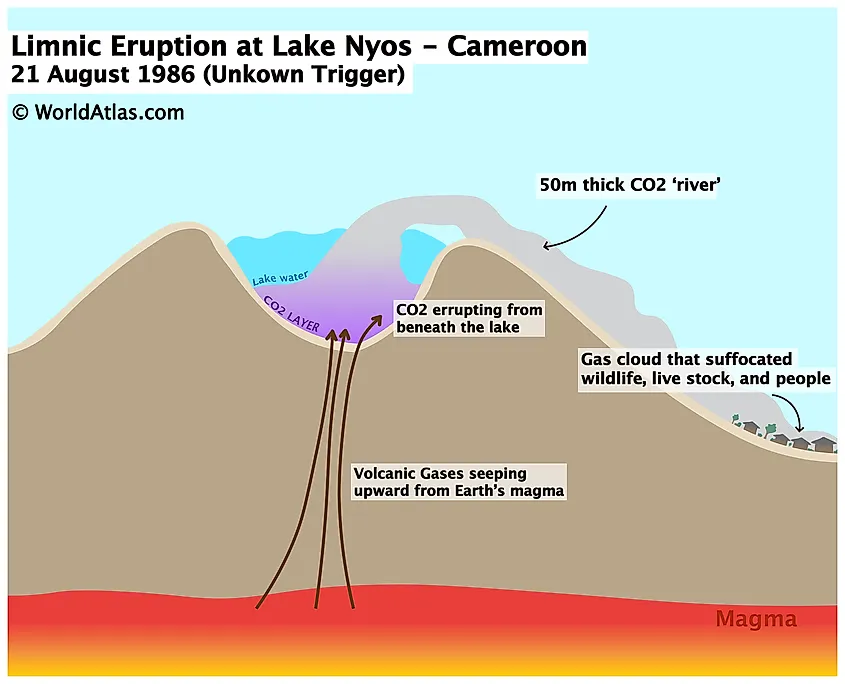

On the night of August 21, 1986, a strange silence fell over the valleys of northwestern Cameroon. Earlier that day, villagers around Lake Nyos had seen nothing unusual — the lake was calm, the air still. But by morning, more than 1,700 people were dead, along with thousands of livestock. An invisible cloud of carbon dioxide had erupted from the lake’s depths, rolling downhill like a ghostly tide and suffocating everything in its path. The culprit wasn’t war or disease, but geology: volcanic gases had seeped up from deep within the Earth, accumulating at the lake’s bottom until the pressure became too much. It was the deadliest known limnic eruption in history — and a warning that some bodies of water contain more than fish and sediment.

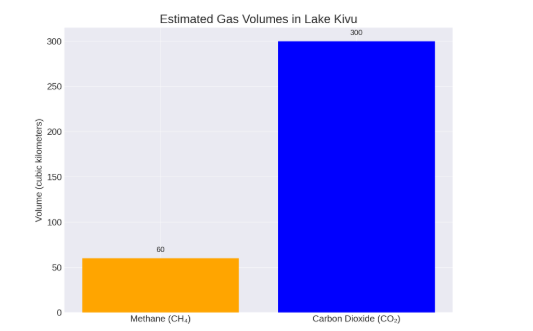

Lake Kivu, nestled in the heart of Africa between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, is serene on the surface—but conceals one of the most volatile energy stores in the world. Trapped beneath its 485-meter depths are massive volumes of carbon dioxide and methane gas: an estimated 300 cubic kilometers of CO₂ and 60 cubic kilometers of methane. These gases pose a dual threat and opportunity: a potential limnic eruption that could suffocate millions, and a vast, underutilized energy reserve that could power a nation.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Monetary Skeptic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.