"I think it’s going to create value and be of great strategic importance.” Treasury Scott Bessent

The notion of saving for a rainy day isn’t some modern invention—it's a practice as old as civilization itself. From the granaries of ancient Egypt to the sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) of today, the fundamental idea has always been to secure a nation’s wealth for the future, ensuring stability and control during uncertain times. Ancient empires didn’t just hoard their wealth for the sake of it—they stored it strategically, much like modern SWFs do today.

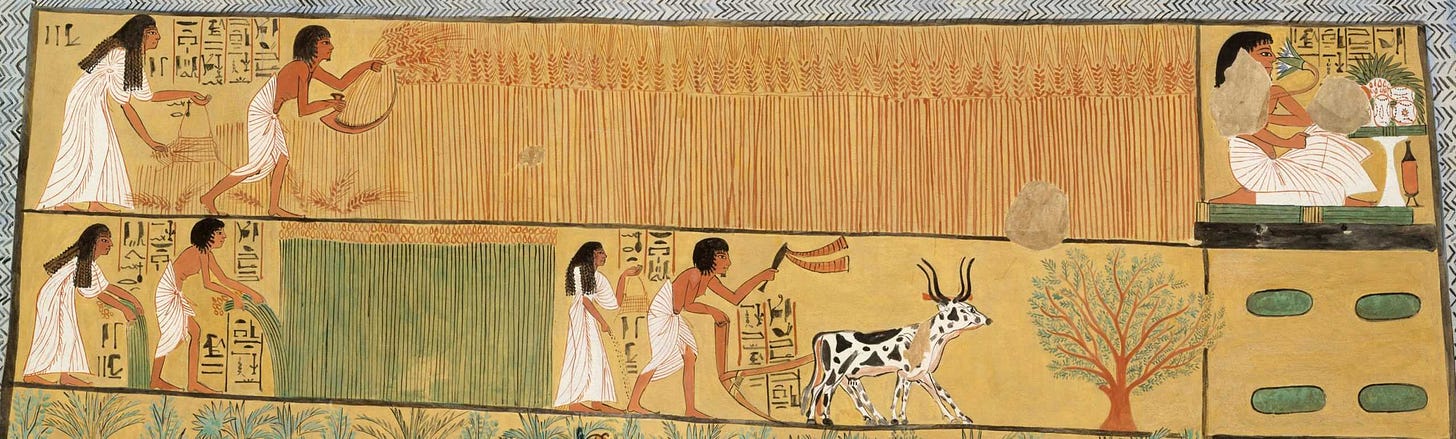

Take ancient Egypt, for example. The Pharaohs ruled not only with political might but also through control of vast grain reserves. These weren’t just for feeding the masses during times of famine; they were an essential tool of power. Granaries across Egypt stored surplus grain, ensuring food security, stabilizing prices, and, importantly, maintaining loyalty among the people. And when times were good, Egypt traded its grain to neighboring regions, further consolidating its wealth and influence. The Pharaohs didn’t stop there—they also controlled gold, much of it sourced from Nubia. This gold funded everything from religious monuments to military expeditions, and it was managed through royal treasuries—early versions of the sovereign wealth funds we know today. Surplus wealth was stored for future use, whether for political leverage or strategic military needs.

In Mesopotamia, particularly in Sumer, the system wasn’t all that different. The Sumerians relied on agriculture, but more importantly, they controlled the irrigation systems that made that agriculture possible. Surpluses were stored and redistributed in times of need, which functioned much like how modern SWFs use resource income to stabilize economies today. It wasn’t just about survival—it was about power and control.

Then came the Achaemenid Empire, under rulers like Cyrus the Great and Darius I. The Persians controlled vast territories rich in gold, silver, and other valuable resources, much of which was acquired through tribute from conquered regions. This tribute was stored in treasuries and used for military campaigns, infrastructure projects, and the lavish lifestyle of the rulers. These treasuries were the earliest forms of sovereign wealth funds—pooled wealth set aside for strategic purposes, just as modern SWFs do today.

And let’s not forget the Romans. As the Roman Empire expanded, so did its wealth. Tribute flowed in from conquered regions, taxes were levied from across the empire, and this wealth was reinvested into the empire. Roads, aqueducts, public baths—these infrastructure projects solidified the long-term economic stability of Rome. The Roman Empire wasn’t just surviving; it was thriving by wisely reinvesting its wealth into infrastructure, ensuring its longevity.

But while ancient civilizations focused on tangible assets—land, grain, gold—modern sovereign wealth funds are far more sophisticated. Today’s SWFs manage diversified portfolios consisting of stocks, bonds, real estate, and private equity. But the underlying concept remains the same: accumulate surplus resources and put them to work for the future.

The world of sovereign wealth funds as we know it today traces its roots back to Kuwait. In 1953, Kuwait established the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA), the world’s first SWF. Back then, the global oil boom was still on the horizon, but Kuwait’s leadership had the foresight to realize that oil wealth wouldn’t last forever. The KIA was established to ensure that the country’s prosperity would extend beyond the oil fields, setting the stage for the SWF model we see today.

But let’s not get too sentimental about Kuwait’s motives. The KIA wasn’t born out of altruism—it was a strategic move. Kuwait understood that relying solely on oil was unsustainable. The KIA’s purpose was to safeguard the nation’s wealth, avoiding the boom-and-bust cycle of commodity prices and insulating the country from inflation that often plagues resource-dependent economies. It was a shrewd, strategic move that would lay the foundation for the SWFs of today.

In the modern era, SWFs are powerhouses, managing trillions of dollars across the globe. These funds leverage national wealth from natural resources, such as oil and gas, to invest in a diversified portfolio of assets designed to provide long-term economic stability. Here’s a look at the biggest players in the SWF space, ranked by their Assets Under Management (AUM) and the returns they generate:

1. Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG)

AUM: ~$1.3 trillion (2024)

Income: ~$50 billion (2023)

2. Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA)

AUM: ~$1.05 trillion (estimated)

Income: ~$50 billion (estimated)

3. China Investment Corporation (CIC)

AUM: ~$1 trillion (2024)

Income: ~$50 billion (2023)

4. Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA)

AUM: ~$750 billion (estimated)

Income: ~$30-40 billion annually

5. Qatar Investment Authority (QIA)

AUM: ~$450 billion (estimated)

Income: ~$15-25 billion annually

6. GIC (Singapore)

AUM: ~$700 billion (estimated)

Income: ~$30-40 billion annually

7. Temasek Holdings (Singapore)

AUM: ~$380 billion (2024)

Income: ~$20-30 billion annually

8. Hong Kong Monetary Authority Investment Portfolio (HKMA)

AUM: ~$550 billion (2024)

Income: Varies depending on market conditions

9. Russia’s National Wealth Fund (NWF)

AUM: ~$180 billion (2024)

Income: ~$5-10 billion annually

10. Saudi Arabian Public Investment Fund (PIF)

AUM: ~$700 billion (estimated, with plans to grow to $1 trillion by 2025)

Income: ~$20-30 billion annually

The evolution of sovereign wealth funds—from the grain stores of ancient Egypt to the vast portfolios of modern funds—demonstrates the power of strategic wealth management. Countries with abundant natural resources, like oil and gas, are particularly well-positioned to build these wealth pools. Today’s SWFs are global financial giants that not only secure their nation’s future but also influence global markets, ensuring long-term stability in an increasingly volatile world.

It may seem curious to see the United States absent from the list of sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), especially given its dominance as the world’s number one producer of oil and natural gas. But, thanks to a few quirks of the U.S. system—namely, constitutional limitations (which, honestly, are a good thing)—and the fact that much of the nation’s oil and gas production comes from state and private lands, the country doesn't maintain a centralized national SWF. Instead, the wealth generated from these resources often flows into state coffers as royalties. Still, there are notable exceptions to this absence, most of which are found in resource-rich states that have taken it upon themselves to establish their own funds.

The Alaska Permanent Fund is perhaps the most well-known of these state-level SWFs. Founded in 1976, the fund’s purpose is simple but profound: to ensure that Alaska’s oil wealth benefits future generations. With Assets Under Management (AUM) exceeding $80 billion as of 2024, the fund’s main source of revenue is oil royalties from the state’s abundant reserves. Unlike traditional SWFs, which often focus on diversifying national wealth, the Alaska Permanent Fund channels a portion of these revenues directly to its residents in the form of an annual dividend. This makes it not just a fund for the future, but a tool for immediate benefit, an innovative model that serves as an example for other states.

But Alaska isn't the only state to have embraced the concept of a sovereign wealth fund. In New Mexico, the New Mexico Permanent Fund boasts approximately $25 billion in AUM as of 2024. Primarily funded by royalties from oil, gas, and minerals, the fund was established to support public services, particularly education, healthcare, and social welfare. It acts as a long-term savings vehicle, using investments to generate returns and ensure that New Mexico’s natural resource wealth is both preserved and put to work for the benefit of future generations. Like Alaska, New Mexico’s fund helps shield the state from the volatility of resource extraction while ensuring social programs remain well-funded, especially during leaner years.

Texas, ever the powerhouse in terms of energy production, has its own monumental fund: the Texas Permanent School Fund (PSF). As of 2024, the PSF holds about $50 billion in AUM. Established in 1854—, it was created to support public education in the state, primarily through investments in oil and gas royalties, land, equities, and bonds. Over the years, the PSF has become one of the largest state-managed funds in the U.S. and plays a crucial role in funding public schools across Texas. Given its size and influence, the PSF has earned its place as a financial titan, helping secure the future of Texas' education system while providing a stable stream of funding for generations to come.

An article written by Doomberg illustrates the situation perfectly — and I highly recommend you check it out.

In the heart of West Texas, beneath the arid soil, lies a treasure trove of oil and gas—assets under the stewardship of the University of Texas System. The advent of hydraulic fracturing has unlocked unprecedented volumes of crude, with daily extractions reaching millions of gallons. Each barrel extracted contributes to the Permanent University Fund (PUF), a substantial endowment supporting the University of Texas (UT) and Texas A&M University systems. As of August 31, 2024, the PUF’s net assets stood at approximately $ 36.5 billion, earmarked for educational and general purposes.

The financial impact of this resource is evident. In the fiscal year 2024, the UT System received $603 million from the Available University Fund (AUF), with about half allocated to its flagship campus in Austin. This marks a significant increase from the $352 million received in 2011.

With this financial boon administrative expenditures have surged, with the UT System’s general administration costs quadrupling since 2011, reaching $143 million in the most recent academic year. Additionally, the system has committed substantial sums to various initiatives:

$215 million for the acquisition of 300 acres of undeveloped land in Houston, with plans to sell the property following political pushback.

$100 million invested in an in-house educational technology startup that has faced challenges in meeting its objectives.

$141 million allocated for the construction of a 17-story office tower in downtown Austin to accommodate system employees.

These financial decisions highlight the interplay between resource extraction and institutional growth. If we take a look at the sovereign wealth funds of major U.S. states, the combined assets under management (AUM) typically fall somewhere between $200 billion and $250 billion. In contrast, the major university endowments across the country, a rarified club of Ivy League powerhouses and prestigious institutions, collectively hold an estimated $700 billion to $930 billion.

That’s right—state funds, while substantial, are dwarfed by the titanic sums fueling the endowments of these academic behemoths. These figures illustrate the vast, generational wealth that flows through U.S. institutions, much of it secured via investment strategies and resource extraction, not unlike the oil under the Texas soil.

But here’s the kicker: these university endowments essentially function as mini sovereign wealth funds (SWFs). They manage colossal sums of capital with investment strategies that rival those of state-run wealth funds, directing funds into diversified assets, from equities to real estate to natural resources. Endowments are now economic powerhouses in their own right, wielding influence that extends far beyond the walls of their campuses.

Let that sink in: nearly $930 billion is locked up in university endowments, making them the giants of American finance, often outstripping state funds in both scale and influence.

And then there’s Wyoming, with its Wyoming Permanent Mineral Trust Fund. With an AUM of over $8 billion (2024), this fund is directly fueled by the state’s rich mineral resources—primarily oil, gas, and coal. The fund provides financial support for Wyoming’s government, enabling the state to maintain a stable fiscal environment while cushioning its budget against the inevitable ups and downs of commodity prices. While smaller than its counterparts in Alaska or Texas, the Wyoming fund still plays a critical role in managing the state’s wealth for long-term benefit.

When President Donald Trump signed an Executive Order in 2025, it wasn't just another policy shift—it was a bold financial maneuver aimed squarely at reshaping U.S. economic power. The creation of the U.S. Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) isn't come without controversy. On the surface, it appeared to be a simple tool for economic growth—stimulating sectors like technology, energy, and infrastructure. But dig deeper, and the strategic implications are profound.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Monetary Skeptic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.