“The future of global energy security lies in integrated corridors that span continents, connecting producers, transit states, and consumers.” — World Energy Council

In the twilight of the Ottoman Empire, the Berlin–Baghdad Railway was one of the great infrastructure gambits of the modern era. Backed by Imperial Germany, it aimed to connect Europe to the Persian Gulf by rail, bypassing British-controlled sea lanes and securing Berlin’s access to Mesopotamian oil.

To London, this was not just a railway—it was a red line. The British Empire, whose naval dominance anchored its global power, saw the project as a direct challenge to its hegemony over Middle Eastern oil and the Suez Canal, the vital artery to India. The Berlin–Baghdad line would effectively bypass both the Strait of Gibraltar and the Suez Canal, threatening to redraw the commercial and political map of Eurasia in Germany’s favor. Though large segments of the railway were completed, the full route was interrupted by World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Yet its legacy endured: it marked the first modern attempt to convert geography into geopolitical leverage through rail.

Today, Egypt is building on a similar premise: turning geography into power. Through a $23 billion, 2,000-kilometer high-speed rail system, Cairo is constructing more than transport infrastructure. It is creating a continental logistics and energy corridor—linking Sudan’s stranded oil, Libya’s unstable exports, and Egypt’s underused refineries and ports. Egypt positions itself as a land-based alternative to the Suez Canal, a pressure valve for Red Sea disruptions, and a regional backbone for African trade and energy.

Like the Berlin–Baghdad Railway, this is more than steel—it is strategy.

Sudan’s oil sector is in limbo. With output near 57,000 barrels per day (2023), the country depends entirely on Port Sudan for exports—a route increasingly threatened by civil war. Its key refinery, al-Jaili, has been severely damaged, forcing Sudan to import refined fuels despite its crude reserves. Overland transport costs remain high, at $10–15 per barrel by truck, with limited pipeline access.

Egypt’s southern rail extension, especially from Aswan to Wadi Halfa, could change this. Crude from Sudanese fields like Heglig and Melut Basin could be transported by rail to Upper Egypt’s Assiut refinery or onward to ports at Alexandria and Ain Sokhna, bypassing Port Sudan.

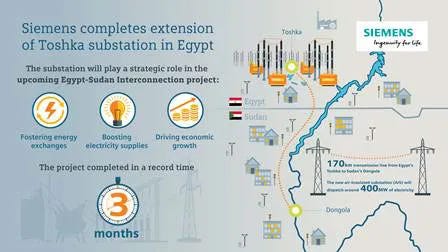

Beyond logistics, Egypt and Sudan are developing an energy barter system—electricity from Egypt for oil from Sudan—via the Toshka–Arqin grid. This lowers Sudan’s energy import costs while providing Egypt with feedstock for its refineries. For investors wary of Sudanese instability, Egypt’s infrastructure offers a safer link to Sudanese oil.

Libya’s oil production stabilized at about 1.2 million barrels per day, but its refining capacity—around 380,000 bpd—is mostly offline. Political fragmentation and frequent port shutdowns at Es Sider and Ras Lanuf leave its oil exports vulnerable.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Monetary Skeptic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.