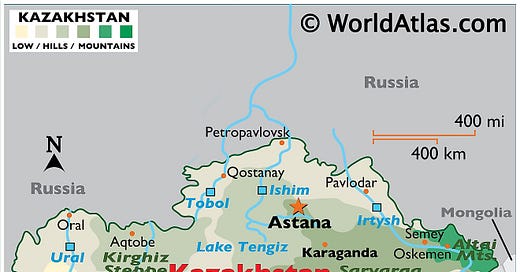

Nestled amidst Russia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, China, and the Caspian Sea lies Kazakhstan, the largest landlocked country globally and ninth-largest in terms of area. Encompassing an expanse that rivals most of Western Europe or two-thirds of the United States, Kazakhstan grapples with extreme climatic conditions due to its landlocked nature and minimal water bodies, primarily the Caspian Sea. Enduring bitterly cold winters and scorching summers, the nation is characterized by vast expanses of cool desert at its core and dry semi-arid regions in the east. Despite these challenges, Kazakhstan boasts significant freshwater resources, including the Syr Darya, fed by glacier melt from the mountains of Kyrgyzstan, and Lake Balkhash, ranked as the 15th largest freshwater lake globally. Additionally, numerous smaller rivers traverse the country, contributing to its water wealth.

The narrative often attributes Kazakhstan's geographical and climatic predicaments solely to climate change. However, a deeper examination reveals that human activities have profoundly influenced the country's landscape, surpassing the impacts of CO2 emissions. Despite ranking 12th globally in both proven oil reserves, boasting 30 billion barrels, and oil production, with 1,897,000 barrels per day, Kazakhstan's development trajectory has left a lasting imprint on its environment. To grasp the roots of this phenomenon and chart the nation's future in the oil industry, we must delve into Kazakhstan's historical landscape transformations.

The Russian Period

The inception of what we now recognize as Kazakhstan dates back to 1613 when the Russian Empire initiated the construction of forts along the northern border to fend off nomadic raids and secure trade routes to China. Over time, these forts evolved into cities, serving to assert Russia's territorial claims over the region. However, Russia's dominion over Kazakhstan came at a cost, as the tumultuous period of the Russian Civil War (1917-1922) between the Whites and the Bolsheviks inflicted significant environmental and ecological damage. The conflict brought about widespread infrastructure destruction and disrupted traditional economic systems, exacerbating environmental degradation. Moreover, the centralized planning inherent to the Soviet regime hindered efficient resource allocation and distribution of goods, further contributing to ecological challenges in the region.

Kazakh famine

The Kazakh famine of 1919-1922, also known as the Turkestan famine, was a tragic episode marked by mass starvation and drought in the Kirghiz ASSR (present-day Kazakhstan) and Turkestan ASSR during the aftermath of the Russian Civil War. Reports estimate that between 400,000 to 750,000 peasants succumbed to famine-related causes, with roughly half of the population facing starvation by 1919. The famine, exacerbated by intermittent droughts and exacerbated by government policies such as Prodrazvyorstka, was part of the broader Russian famine of 1921-22, which claimed up to 10,000,000 lives across the Soviet Union. Epidemics of typhus and malaria further compounded the humanitarian crisis, with significant losses reported in provinces such as Aktyubinsk, Akmola, Kustanai, and Ural. While demographers estimate a death toll of around 400,000, Turar Ryskulov, chairman of the Central Electoral Committee of the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, suggested that the actual figure could be as high as 750,000.

Following the famine, agricultural production in Kazakhstan continued to decline as the Soviet Union implemented collectivization policies in the 1930s to bolster agricultural and industrial output. However, this initiative proved disastrous as it forced nomadic tribes, unfamiliar with grain production, to adopt Soviet-style farming methods. Between 1930 and 1933, an estimated 1.5 million to 2.3 million people perished in famines as a result of these policies, further exacerbating the region's humanitarian crisis.

Virgin Land Project Campine

While the Virgin Lands campaign initially yielded promising results, notably in addressing immediate food shortages, its long-term impact reveals a stark narrative of failure. Despite its grand scale and historic significance, the campaign fell short of Khrushchev's ambitious goal to surpass American grain output by 1960. The arid conditions of the Virgin Land areas posed formidable challenges to monoculture farming, receiving only 200 to 350 mm of rainfall annually, primarily during the critical stages of grain maturation and harvest. Moreover, frequent droughts, short vegetation periods, and harsh climatic fluctuations further compounded agricultural woes. Strong winds exacerbated soil erosion and snow displacement during winter, while the soil's high salt content further hindered agricultural productivity. The extensive monoculture farming practices of the campaign, covering 83% of cropland, led to the depletion of essential nutrients in the soil, exacerbating desertification. Consequently, an estimated 60% of the country's pasture land succumbed to desertification, perpetuating a cycle of declining agricultural production.

Aral Sea

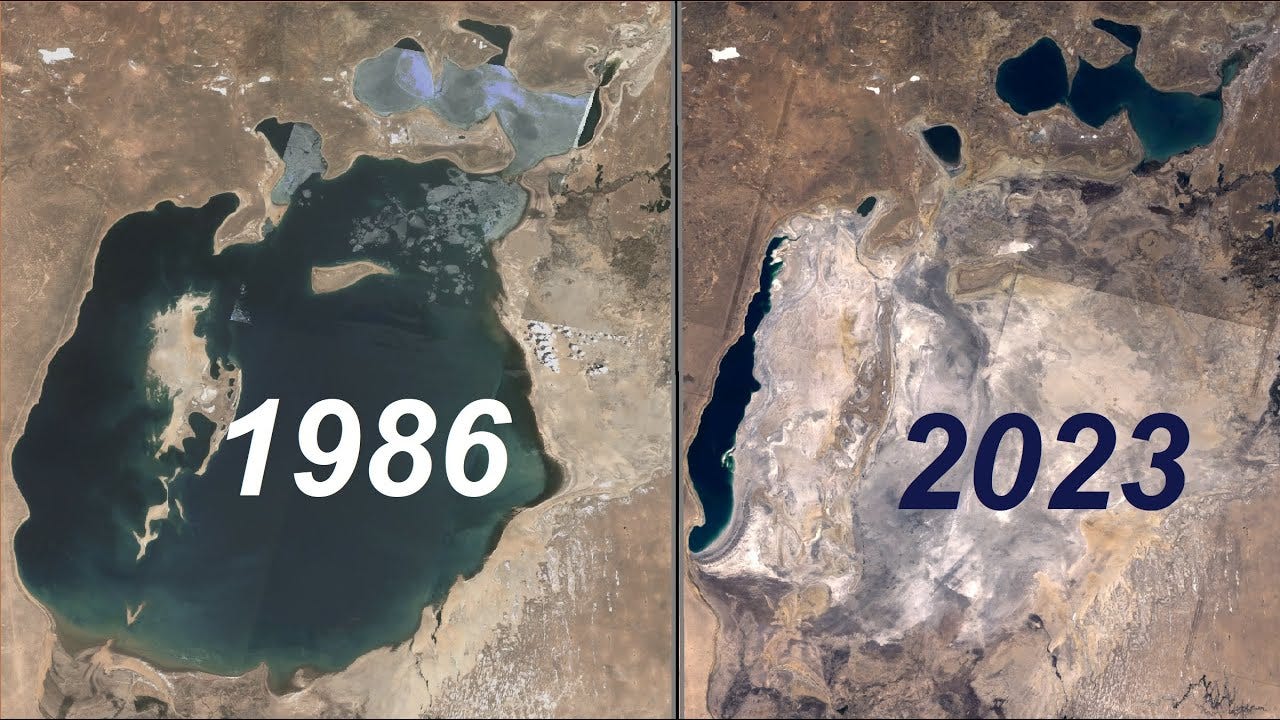

Once ranked as the world's third-largest lake, the Aral Sea, spanning an area comparable to that of West Virginia, stands as a poignant reminder of Soviet intervention. Fed by the Syr Darya from Turkmenistan and the Amu Darya from Tajikistan, originating from glacier melt in the Tian Shan mountains, the sea once thrived as a vital ecosystem. However, Soviet initiatives aimed at transforming Uzbekistan's desert landscape into agricultural land precipitated the sea's demise. Cotton cultivation, a water-intensive crop, became the focal point of Soviet agricultural policy. To facilitate irrigation for cotton fields, extensive canal networks were constructed around the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers, diverting crucial water resources away from the Aral Sea. Consequently, the sea rapidly dwindled, shrinking to a mere fraction—approximately 10%—of its original size. The geographical position of the Aral Sea, situated within a desert landscape, compounded the issue, with high evaporation rates and minimal rainfall exacerbating its depletion.

Imagine provided by NASA

A consequential outcome of the Aral Sea's depletion was the collapse of Kazakhstan's once-thriving fishing industry. As the sea continued to evaporate, its remnants became increasingly saline, rendering it inhospitable to aquatic life and leading to a complete cessation of fishing activities by the 1980s. The ongoing shrinkage of the sea gave rise to a new desert landscape, exacerbating soil erosion and further diminishing agricultural productivity. To compensate for declining yields, the Soviets resorted to excessive use of fertilizers and chemicals in Uzbekistan's cotton fields, resulting in runoff pollution flowing into the Aral Sea. This created a vicious cycle, whereby the saltier desert contributed to soil erosion, prompting increased fertilizer usage, and further exacerbating pollution. The contaminated sea surface, tainted with pesticides and chemicals, generated poisonous dust clouds that blanketed central Asia and Uzbekistan's cotton fields. In a misguided attempt to address these issues, the Soviets intensified chemical applications in Uzbekistan's cotton fields, exacerbating water usage from rivers to flush out salt residues.

Melting glaciers

The Aral Sea historically played a crucial role in regulating Kazakhstan's climate, acting as a buffer against harsh Siberian winds in winter and providing cooling effects in summer. However, the catastrophic decline of the Aral Sea has led to profound environmental repercussions. Today, the region experiences shorter, hotter summers, and colder, longer winters, along with the emergence of poisonous dust clouds and reduced rainfall. The diversion of the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers from the Aral Sea has disrupted the natural evaporative mechanisms, altering precipitation patterns in the Tian Shan Mountains. Furthermore, dust storms generated by northern winds from Siberia have deposited layers of dust on mountain glaciers, accelerating their melting rates. This accelerated melting, estimated to be twelve times faster than before Soviet interventions, exacerbates the depletion of water sources vital for the region's ecosystems and communities.

Caspian Oil

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan emerged from its Soviet legacy and embarked on a journey of economic revival. With newfound independence, the nation strategically opened up its oil and uranium sectors to global markets. However, decades of Soviet isolationism had left Kazakhstan's natural resources largely untapped. In a landmark development in 2000, a consortium led by Eni, BP, Royal Shell, TotalEnergies, in collaboration with the Kazakh government, unveiled the discovery of the Kashagan Field, one of the largest oil finds in recent decades. With estimated reserves of 13 billion barrels of crude oil valued at $116 billion, the Kashagan Field represented a monumental leap in Kazakhstan's energy prospects. The construction of oil pipelines, facilitated ironically by Al Gore, connected Kazakhstan's Caspian oil to lucrative markets in China and the Russian port of Novorossiysk, yielding a staggering $35 billion in revenue in 2022 alone. Since gaining independence, Kazakhstan has attracted over $370 billion in foreign direct investment, predominantly directed towards bolstering its oil infrastructure. This influx of capital has propelled Kazakhstan to become the largest economy in Central Asia, boasting the highest income per capita in the region. The economic windfall from oil dividends is reflected in the country's demographics, with a notable shift from a declining birth rate of 1.8 births during Soviet occupation to a robust 3.3 births, a phenomenon defying modern demographic trends and correlating strongly with GDP growth.

In conclusion

Kazakhstan presents a stark departure from the prevailing narrative on climate change. While acknowledging the reality of climate change and its human-induced effects, the nation's robust oil production industry offers a contrasting perspective. Kazakhstan grapples with various environmental concerns such as famine, desertification, drought, and declining agriculture, not primarily due to CO2 emissions but largely because of past central government planning, notably during the communist era. This serves as a poignant reminder that misallocation of human capital and financial resources can inflict more significant damage on the climate than carbon emissions.

Excellent Post.

Note that Ukraine has large reserves of frackable shale and other resources including big agriculture.

This is why I like substack - I learn new things every day. Before, I could hardly find Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Krygyzstan. As for the history, it's horrible but good to be reminded how millions of people died under Soviet central planning. Meanwhile, the main point of the post is well taken - that climate change has very little to do with the .04% of CO2 in our atmosphere.